Ansikte mot ansikte

(Anna Cederberg-Orreteg)

Minnena ser mig

(Anna Cederberg-Orreteg)

Resan mot C

(Bo Holten)

Stenarna

(Kaj-Erik Gustafsson)

Sammanhang

(Kaj-Erik Gustafsson)

Elegi

(Michael Waldenby)

Två städer

(Georg Riedel)

November i forna DDR

(Georg Riedel)

Tystnad

(Georg Riedel)

Som att vara barn

(Georg Riedel)

Midvinter

(Georg Riedel)

Minusgrader

(Catharina Backman)

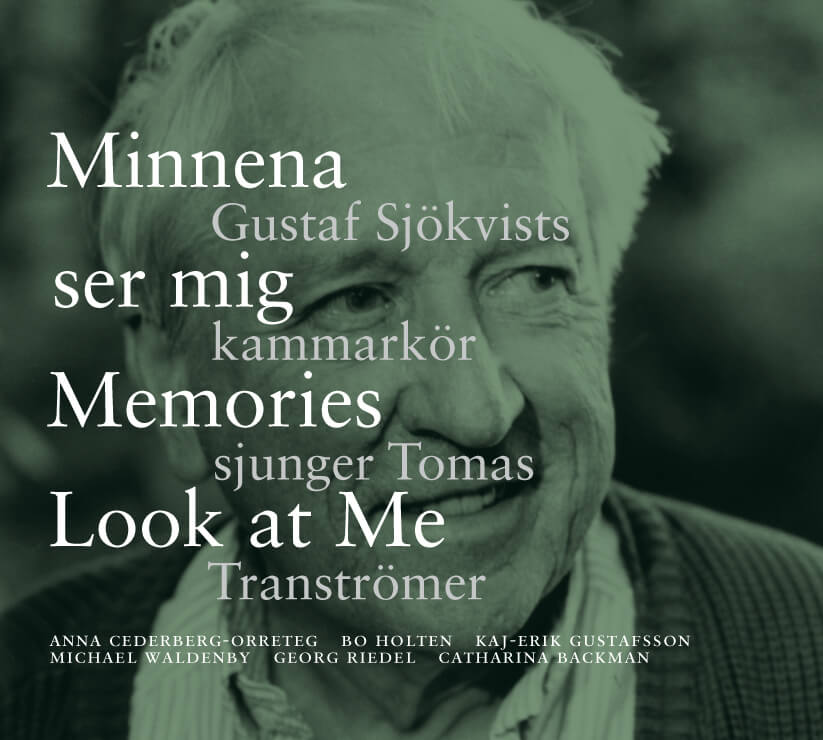

Homage to Tomas Tranströmer

At some point in his life, Tomas Tranströmer supposedly faced a choice: music or poetry.

Indeed, it can certainly be said that he chose poetry, but that does not mean that he excluded music; on the contrary, it became an ever present force in his writings. As a source of inspiration and motif – particularly with regard to the magnificent portraits of composers Grieg, Balakirev, Schubert, Liszt – but also in his frequent references to music. And, maybe most importantly, through the influence on the poetical language, an influence that defies description. It is not conveyed by purely semantic means, but is sensed in the melodics, rhythmics and implied dynamics of the poems. Furthermore, acoustics in general play an extremely important role in Tranströmer’s poetry. This is characterized by an attentively listening attitude – a kind of acoustics that paradoxically seems to include what the poet has called “the mute half of music”. Ever since his first collection 17 Poems (17 dikter, 1954) you come across wordings that call forth a music inherent to all of nature/history/cosmos. “The bronzeage trumpet’s outlawed note” is heard, tree roots sound like copper lures, out of the wintry dusk rises “a tremolo from hidden instruments”. In a poem in The Wild Market-Square (Det vilda torget, 1983) the station hand’s sledgehammer against the wheels of the train creates an unimaginably sonorous tone: “peal of cathedral bells, a sailingroundtheworld peal”. In Transtömer, the immense, unconditional and universal tone seems to dwell inside silence. During an intermission in an organ concerto, it grows out of a silence where otherwise imperceptible sounds surface. A state ensues where a kind of acoustic chain reaction is being suggested, and finally everything is singing. With regard to the poem “Brief Pause in the Organ Recital” (”Kort paus i orgelkonserten”, Det vilda torget) Staffan Bergsten keenly writes: “He resides enveloped in the cosmic order, in the quiet rooms of lifegiving nature and the slumbering spirit. During the intermission, when all is silent, he hears the beating of a pulse that is his own, Society’s and the world’s.”

In Tranströmer’s poetry there are many references to his own playing. In an early poem he describes how he is seated at the piano “after a dark day”, and finds it a relief that “The keys are willing. Soft hammers strike.” I have good reason to believe that Tomas Tranströmer, every day of his life, whenever possible, has spent time at the piano.

And in the last few years, he has often performed in public as a pianist, mainly playing music written expressly for him: piano pieces for the left hand – the illness that befell him in 1990 has not prevented him from playing; on the contrary, one gets the impression that playing the piano has become an even more important means of expression. And the music immanent in Tranströmer’s poetry has inspired several composers, of which this record is a euphonious proof.

Bengt Emil Johnson

English translation: Nicklas Källén